Two months into last year's pandemic lockdowns, the entrepreneur Collin Wallace stumbled upon a financial blog post questioning the viability of food-delivery operators like his former employer, Grubhub.

"How did we get to a place where billions of dollars are exchanged in millions of business transactions but there are no winners?" the author, Ranjan Roy, wrote.

The post elicited a firestorm of comments. Many said third-party delivery operators were hurting restaurants by charging them hefty commission fees of up to 30% per order and listing locations on their apps without permission.

Wallace, who sold his food-ordering solution, FanGo, to Grubhub a decade ago when he was 25, couldn't help but weigh in. The former head of innovation at Grubhub said there's "truth behind many of these claims" because he had witnessed it firsthand.

"Sadly, I invented a lot of the food delivery technologies that are now being used for evil," he wrote last year.

He said delivery operators are like payday lenders for restaurants. They give operators "the sensation of cash flow" but at the expense of their long-term financial stability, he wrote.

"Once you 'take out this loan' you will never pay it back, and it will ultimately kill your business," he wrote.

It was a seminal moment for Wallace — one in which he unloaded years of angst about his contribution to the disruption of restaurants with the emergence of food delivery.

"It was one of those late-night comments that you make out of frustration," Wallace told Insider in a recent interview.

His frustration with the delivery industry erupted again this month when Gruhub introduced Grubhub Direct, billed as a commission-free online ordering tool for independent restaurants. It allows restaurants with fewer than 25 locations to build customizable, direct online-ordering websites.

During the peak of the pandemic, rivals DoorDash and Uber Eats made similar moves to offer select e-commerce tools for free to restaurants.

Wallace, who now owns another food tech marketing startup in the Bay Area, doesn't buy their sincerity. Restaurants need more than a functioning e-commerce website to succeed, he said.

"We know that the only way they can control their fate is if they control their relationship with the customers," Wallace wrote this week on his company's website. Delivery operators say they are trying to help restaurants

Grubhub, DoorDash, and Uber Eats declined to comment on Wallace's criticism of the delivery industry. Representatives said their services for restaurants during the pandemic speak for themselves.

In addition to offering Grubhub Direct, introduced on May 12, Grubhub is waiving Direct's $49 per month web hosting fee through April 2022.

Since July, Uber Eats has offered all restaurants the ability to add online ordering (delivery or pickup) to their websites. The option is commission free through June 30 and comes with access to consumer data if diners choose to share their information with restaurants.

The market leader DoorDash introduced tiered commission rates in late April, ranging from 15% to 30%, for local restaurants with 75 locations or fewer. Through its last-mile delivery and online ordering services like DoorDash Drive and DoorDash Storefront, restaurants have access to customer information, the company said.

"They are giving this technology away because it is not valuable by itself, and won't actually help restaurants be more competitive," Wallace wrote this week.

He said the "little-known secret" is that the most valuable part of the delivery business is access to customer information. Historically third-party operators have not been giving that lucrative information to restaurant partners, but delivery operators say some of these new services come with access to data.

One of the 'grandfathers of modern food delivery'

Wallace created FanGo in 2006 while studying electrical and mechanical engineering at Georgia Tech.

He texted a friend one day asking to bring a snack before he hit lacrosse practice after a three-hour lecture with no time in between to eat. That's when the idea hit him.

"What an interesting idea: Build a text message and have people bring me food," he said. Wallace immediately began coding a text-ordering program to work on Blackberry mobile phones. iPhones were not around. The applet system was crude, but it served its purpose.

The applet processed the meal order by converting it to binary numbers sent as a text message to a server. The server would decode the order and send a fax to the restaurant.

"I literally spent that whole semester building this in class," he said. "I think I got a B because I wasn't really paying attention."

Wallace spent the next few years piloting FanGo in various venues, including airports, sports arenas, casinos, and hotels. When the iPhone debuted in 2007, the technology became easier to use and more accessible, thanks to Apple's App Store. He later added payment processing, a crucial breakthrough because it allowed for a cashless transaction.

In 2011, Grubhub, which started off as a company that digitized paper menus, took notice of Wallace's technology.

"We love the technology. We want the technology. We want it exclusively," Wallace recalls Grubhub telling him.

He didn't disclose the exact terms of the sale, but Wallace said it was not a difficult deal to make for a 25-year-old. He made enough cash to take care of his family and realized his dreams of sailing around the world and attending business school at Stanford, he told Insider.

The Economist earlier this year called the serial food entrepreneur one of the "grandfathers of modern food delivery."

The recognition made Wallace think about how the food-delivery industry has evolved since he bootstrapped FanGo in college.

"The emphasis has been on generating growth at all cost and disruption at all cost. And there's a point where disruption starts to become exploitation," Wallace said.

Any regrets selling to Gruhub?

Though he questions the motives of delivery operators, Wallace said he doesn't regret the decision to sell FanGo because he didn't fully understand how his early technology would eventually be used.

At 36, he said he's a lot smarter about his business decisions.

"Now it's more important for me to be able to control how my ideas and how my inventions are used," Wallace said.

That's why Wallace and his co-founder Ashutosh Joshi built a marketing tool that's an antidote to third-party delivery operators owning the customer relationship.

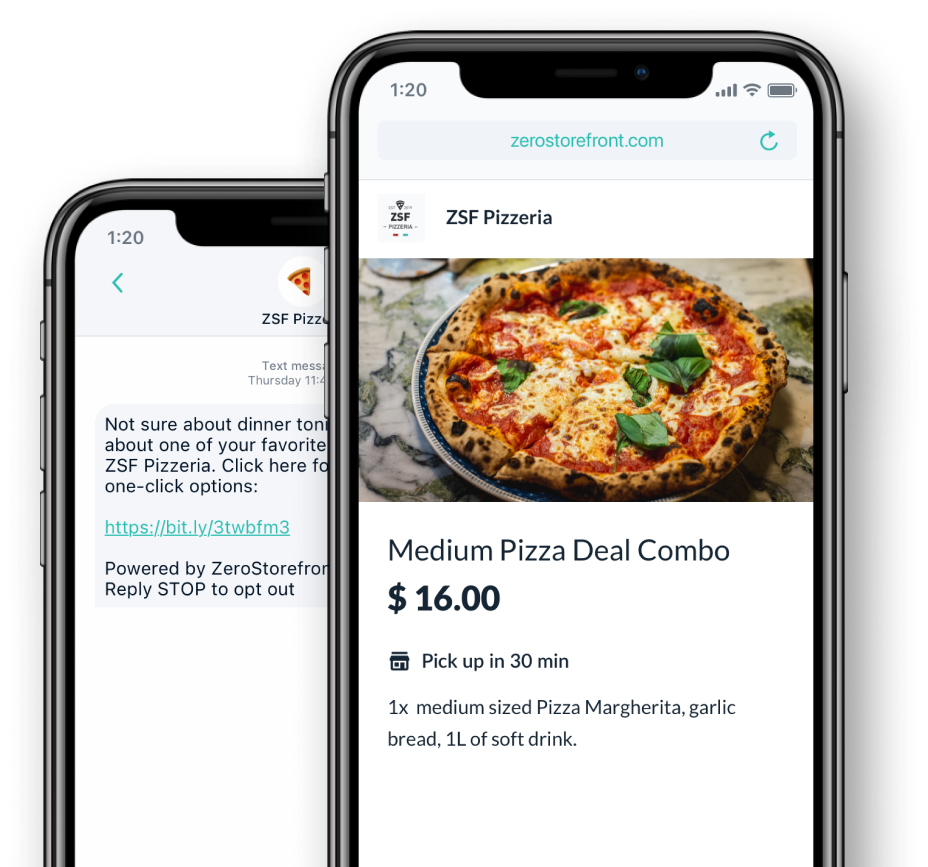

ZeroStorefront, backed by the startup seed funder Y Combinator, provides customer data to small businesses so they can market directly to guests through texting.

"The best possible way to connect with customers is through messaging," he wrote on his site. "Smart restaurant operators now have an opportunity to build a portfolio of the best technology solutions, but nailing the relationship with the customer is the most critical step."

Though he's moved on, every so often Wallace is reminded of his year-long stint at Grubhub.

While an innovation leader at Grubhub, Wallace helped launch those infamous tablets that restaurants use to process incoming delivery orders. Every so often, when he walks into a restaurant, he'll hear the "ping" of an order coming through a tablet.

It gives him pause.

"There's definitely pride in having built something that people use. I think there's also a little bit of anxiety around thinking, 'I hope they use it carefully.'"

Axel Springer, Insider Inc.'s parent company, is an investor in Uber.